|

|

By Unity Powell

On a gray, rainy day at Cleveland School of the Arts, a choir of teens practiced an upbeat medley of songs accompanied by piano. Dr. David M. Thomas stood, watching his colleague lead the students through the arrangement. While passing through to get to his class, it was obvious that his presence had significance. He patted his feet and bobbed his head, smiling.

The magic of music and its ability to unite people is a sentiment that defines Thomas’s decades-spanning career as a performer, educator, and composer. He has always used music as a means of connection and change. His journey from small-town origins to becoming a world-class versatile musical leader is a tale of purpose.

Born in Youngstown, Ohio, and raised in the suburb of Hubbard, he was surrounded by the rhythms of family and faith. His parents migrated from Alabama and brought the Southern traditions with them. They grew their food, kept chickens, cultivated community, and stressed the importance of church, a space in which music was a centerpiece.

Youngstown was once the “steel city” in its prime. “The steel mills were all that mattered,” Thomas said. “It was how my father earned a living, but it wasn’t my path.” By the 1970s, when the industry was declining, that environment turned Thomas’ pursuit of music into a leap of faith.

Thomas’s first performance was in the fifth grade when his mother had him play a hymn for worshippers. “I didn’t realize I had a natural talent,” he said. “It was just fun to play something people can sing to.” That excitement turned into passion, even as he was teased for it by his sports-loving brothers.

By high school, music was what drew his interest. His band teacher discovered he had perfect pitch, which is the ability to identify musical notes just by hearing them. “That teacher made the difference for me,” Thomas said. “He proved to me that music could be my future.”

Thomas studied at Youngstown State University’s Dana School of Music, where he developed his talents.

He formed the band “Neon Tranquility,” which landed a record deal and recorded at the legendary Sigma Sound Studios in Philadelphia. They later toured with Major Harris, who had a hit with “Love Won’t Let Me Wait,” which dominated the charts, and later with Rose Royce during their “Car Wash” period. Playing alongside legends like Dizzy Gillespie and Luther Vandross was exhilarating, but the industry’s instability loomed large.

For many touring musicians in the 1970s, life on the road was a double-edged sword. The glamour of performing with top acts often came with financial instability, grueling schedules, and physical risks. This reality came to fruition for Thomas during a heavy snowstorm in Virginia. The bus rattled along the icy highway, its headlights barely cutting through the thickness of snow. The storm arrived quickly, covering the mountains. Thomas was sitting by the window, holding the arm rest tight, at every turn he felt his nervousness grow. “This might be it,” he thought.

It wasn’t only the weather that chilled him; it was the uncertainty after each tour, the long stretches of waiting for the next call, and the nagging sense that his dream might leave him stranded, figuratively and literally. To step away from touring was difficult but Thomas wanted more stability. He returned to college, earning his degree in music education from Case Western Reserve University.

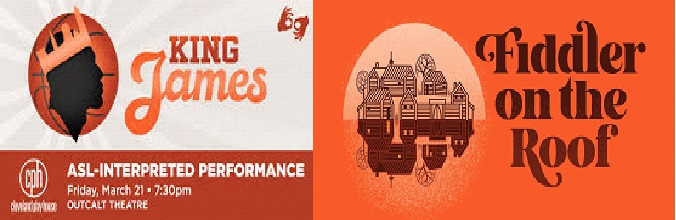

His versatility included major productions, as music director for Karamu House’s Black Nativity. He reimagined the score by adding R&B and hip-hop flavors while preserving the original vision of Langston Hughes. “It’s about respecting tradition and moving it forward,” he said. Now, the production has made its way to Cleveland’s famed Playhouse Square allowing access to a much larger audience.

Thomas’ students are working in shows on Broadway like Hamilton and students who are music directors for big performing art groups across the country.

Evelyn Wright, jazz vocalist, and long-time collaborator reflected on Thomas as a mentor and his work with under-represented youth. “He’s always wanting to remain engaged, stay connected to teaching, making sure that the kids have a pathway to move on. Walter Barnes went on to play with Babyface.”

At home, Thomas is simply a dad. Married for decades, he shares a life rooted in faith with his wife, whom he met in church. Together, they raised three daughters, each finding her unique path: one works as a doctor in Cleveland, another as a banker in Toledo, and the third as a choreographer and dance educator in California.

Parenthood brought a new dimension to his life, shifting his priorities and grounding his decisions. “You can’t replace the connection with your kids,” he says. Even as music remained central to his career, he appreciated the everyday moments.

Thomas has overcome personal struggles. He was deeply affected by the deaths of his parents; his father, 93, and his mother, 96. “You’re never fully prepared,” he said, “but just knowing it’s coming allows you to grasp some strength.”

His music, including arrangements based on his mother’s favorite hymn, “Amazing Grace,” is a testament to their legacy. His artistry was molded, he explained, by grief. “It alters how you make things. It gives it a new layer, a new type of passion.” This philosophy resonates throughout much of his work, from compositions for orchestras to the fanfare he wrote for his daughter’s wedding.

Thomas is a vibrant force in Cleveland’s arts community. Whether leading a choir, creating original works, or motivating young performers, he takes each project with the same enthusiasm he had back in the fifth grade, as a boy playing his first hymn. “Music is a means of connection, healing, and celebration,” he said. “That’s why I do what I do.”