|

|

By Ajah Hales

Always separate, never equal: Black Americans’ 300-year struggle for upward economic mobility

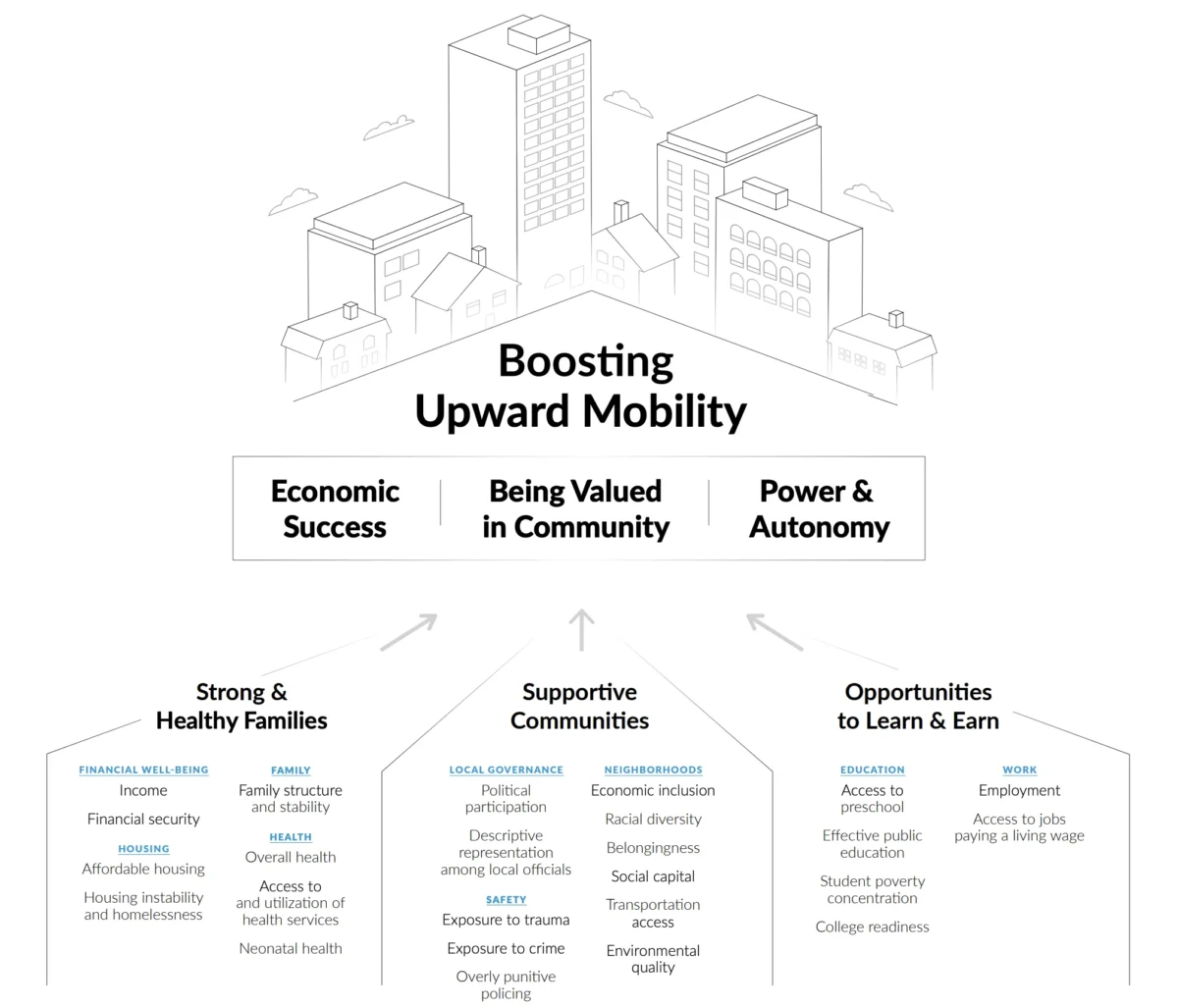

In 2011, Pew Charitable Research Trust released a study on economic mobility in the United States. This study remains one of the most comprehensive data collections on American wealth building. According to the data, access to education, functional family structure, and maintaining savings are the key drivers of upward economic mobility.

Fourteen years later, economists and other sociocultural researchers found that none of these key drivers benefit Black Americans in the same way that they benefit white Americans. Despite high levels of educational attainment, the Black white American wealth gap is greater now than it was in 1980.

So, what are the drivers and disruptors of Black economic mobility in the United States? How have systemic issues like redlining, predatory lending, and lack of access to capital impacted wealth-building Opportunities for Black Americans, and what, if anything, can be done about it?

Black Codes–building the racial wealth gap

To truly understand the roots of the racial wealth gap, go back nearly 400 years. Although the American South was credited with the creation of Black codes starting in 1865, after the Civil War, codified ordinances barring Black Americans’ access to opportunity predate the founding of America.

Some of the earliest recorded Black codes were established by Dutch colonizers in New Amsterdam, which is now called New York. In 1644, the Dutch West India Company ruled that free Blacks living in the colonies had to pay an annual fee for their freedom. Missing a payment meant returning to chains. Additionally, free Blacks were compelled to work for the company “at any time it is requested.”

English colonizers had even stricter rules for enslaved and free Black people. Their codes determined who Black people could live around, work with, and socialize with. One Pennsylvania ordinance from the 1700s prohibited Black people from assembling in groups of four or more.

After the Revolutionary War, even free states like Ohio had Black codes that stripped Black Americans of their rights. Before Ohio became a state in 1803, Black men had the right to vote in the Ohio Territory. After the incorporation of the state, Black people could no longer vote or testify in court. They had to register as free persons at the local courthouse to be able to work in Ohio. Any business owners caught employing unregistered Blacks were fined $50, the equivalent of $1,200 in today’s dollars.

Black Ohioans paid taxes, but weren’t allowed to send their children to public schools. Black settlers who wanted to stay in Ohio had to have two white Ohioans post a $500 bond at the local courthouse, guaranteeing their good behavior, around $13,000 in today’s dollars.

Whether they lived in the North or the South, Black Americans were systematically barred from access to education and the ability to maintain savings, effectively keeping generational wealth for whites only.

Land ownership

Another key driver of generational wealth is land ownership. At the end of the Civil War in 1865, Black Americans were no longer enslaved, but they were never paid for hundreds of years of free labor. In 1865, 20 Black leaders met with Union General William T. Sherman and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton to discuss giving free Black Americans 400,000 acres of coastal land in South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. Each family would receive a plot of 40 acres (the mule came later).

This type of land grant was common in the 1800s. Remember the game Oregon Trail? It was based on the Homestead Act of 1862, which gave white Americans 160-acre plots to ”settle the West.” Land grants were also given to over 100 colleges and universities, including Ohio State University, allowing Americans to benefit from public colleges.

Despite Sherman’s Field Order 15 authorizing land grants for newly freed Black Americans, the Federal Government never made good on its promise. Black Americans were forced to sign labor contracts with their former enslavers or face slavery by another name–convict leasing. Black Americans without proof of employment could be arrested for vagrancy and sold to individuals and companies to “pay their debt to society.”

Even though the odds were stacked against them, some Black Americans accumulated enough wealth to “move on up.” These citizens banded together to create Black towns, only to see these cities destroyed by their white neighbors, drowned under reservoirs or man-made lakes, or stolen through eminent domain.

These early acts of racial violence and discrimination laid the foundation for more modern exploitative systems like redlining, contract lending, and subprime lending that continue to devastate the Black community to this day.

Next month, a closer look will be taken at how legal and de facto racial discrimination from the Civil Rights Era going forward has shaped the Black American economy that exists today, and what can be done to ensure an economic future that looks different than the past.