|

|

By Ajah Hales

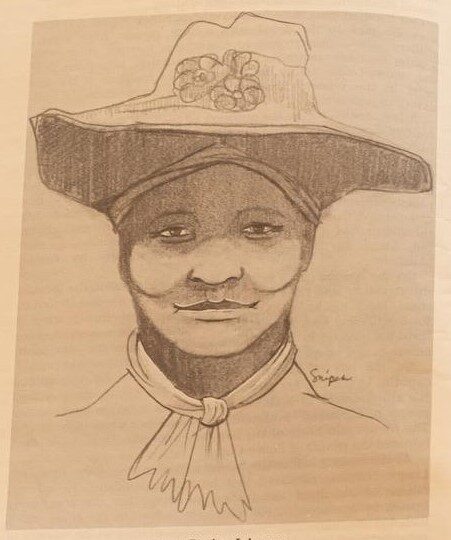

On January 19, 1861, Sara Lucinda Bagby Johnson was arrested in Cleveland. Her crime? Escaping the Virginia plantation where she had been enslaved and starting a new life in Ohio, a free state. Sara was the last person who returned to slavery through the Fugitive Slave Act.

Before 1850, enslaved Black people could escape to free states like Ohio and Pennsylvania and be recognized as free. However, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 changed everything. The law allowed enslavers to reclaim escaped individuals anywhere in the U.S. with only a sworn statement of ownership and a description. A U.S. Marshal could deputize anyone to assist in the capture.

Sara’s enslaver, William Goshorn, took the unusual step of traveling 150 miles to reclaim her himself. What motivated him, and what can we learn from Sara’s legacy today?

Who Was Sara Lucy Bagby Johnson?

Sara, often called Lucy, was born around 1843, but little is known about her early childhood. Many formerly enslaved people couldn’t remember their birth dates because enslavers rarely kept such records. Lucy was sold to John Goshorn at about nine years old for $600, which would be about $22,000 today. At 14, Lucy was passed on as a gift to Goshorn’s son, William.

Historical research suggests Lucy’s life under William was harsh. By 1860, Lucy had discovered she was pregnant and heard rumors that William planned to sell her to Cuba. These factors likely fueled her decision to run away.

A New Life in Cleveland

Lucy’s journey took her to Cleveland, where she arrived alone, likely having lost her baby along the way. Once in Cleveland, she worked as a maid for Congressman Albert G. Riddle, an abolitionist and lawyer who played a role in the Oberlin-Wellington rescue case. Later, she worked for William Smith, another abolitionist, and eventually for Lucius A. Benton, a wealthy jeweler.

Reports about Lucy’s life in Cleveland are conflicting. Some say she was well-treated and liked by her employers, while others suggest she felt bitterness about her treatment. Some claim Lucy stayed in Cleveland voluntarily, while others believe her abolitionist friends persuaded her not to go to Canada, a decision she later regretted.

Regardless of these conflicting accounts, Lucy found powerful friends in Cleveland. Many were prominent abolitionists, including her lawyer, Rufus P. Spaulding. However, these influential supporters could not save her from William Goshorn and the U.S. Marshal he enlisted.

The Politics of Abolition

Lucy’s trial was politically significant. Cleveland was known for its abolitionist stance, while Goshorn was a Southern Democrat and a city councilman in Wheeling, Virginia. He hated Cleveland, calling it “the worst abolitionist hole in the United States.” Goshorn saw Lucy’s case as an opportunity to test Cleveland’s commitment to abolition.

Two years earlier, 37 Oberlin abolitionists had helped free John Price from the Fugitive Slave Act, making the city a target for Southern enslavers. Goshorn was determined to make an example of Cleveland. He traveled to the city personally to ensure Lucy’s capture, perhaps in part to prove a point to abolitionists.

Local abolitionists raised $1,200, double Lucy’s purchase price, in an attempt to buy her freedom. But Goshorn refused, indicating that once he returned her to Virginia, he might consider selling her. In a last-ditch effort, abolitionists planned to ambush the train carrying Lucy, disconnecting her car. This tactic had worked before in Oberlin, but the train conductor did not stop until they were in a slave state.

Sold Down the River and Back Again

When Lucy arrived in Virginia, she was held on the plantation of Goshorn’s cousin. Her escape to Cuba, however, was delayed. As she traveled south toward her fate, a Union officer rescued her in West Fayetteville, Tennessee.

Ironically, Goshorn was arrested in 1862 for refusing to sign a loyalty oath to the Union, becoming a fugitive himself. Lucy, now free, returned to Ohio. She moved to Athens, where she married a Union soldier, George Johnson. Two years later, she returned to Cleveland, where she lived the rest of her life. Lucy worked as a live-in domestic and later settled on Cleveland’s east side.

Lucy passed away in 1906 in her early 60s, outliving the average life expectancy for Black Americans at the time. George Johnson passed away a decade later.

Lucy’s Legacy

Sara Lucy Bagby Johnson’s story is part of Cleveland’s abolitionist history. For many years, Lucy’s grave remained unmarked. However, Michelle Day, a historian at Woodland Cemetery, submitted her gravesite to the National Park Service’s registry of historic Underground Railroad sites in 2015. The site was accepted, and Lucy’s legacy was finally recognized.

Michelle Day has worked tirelessly to bring attention to Lucy’s story. “She’s an amazing, remarkable woman,” Day says, “a major part of Cleveland history that was never taught in schools.” Day hopes to share Lucy’s story with a wider audience, through presentations and collaborations with local organizations like the Cleveland Public Library.

You can visit Lucy’s grave at Woodland Cemetery in Cleveland, located in Section D3, Tier 1, Grave 25. It is a place where we can remember the courage and perseverance of a woman who fought for her freedom—and whose legacy continues to inspire us today.