|

|

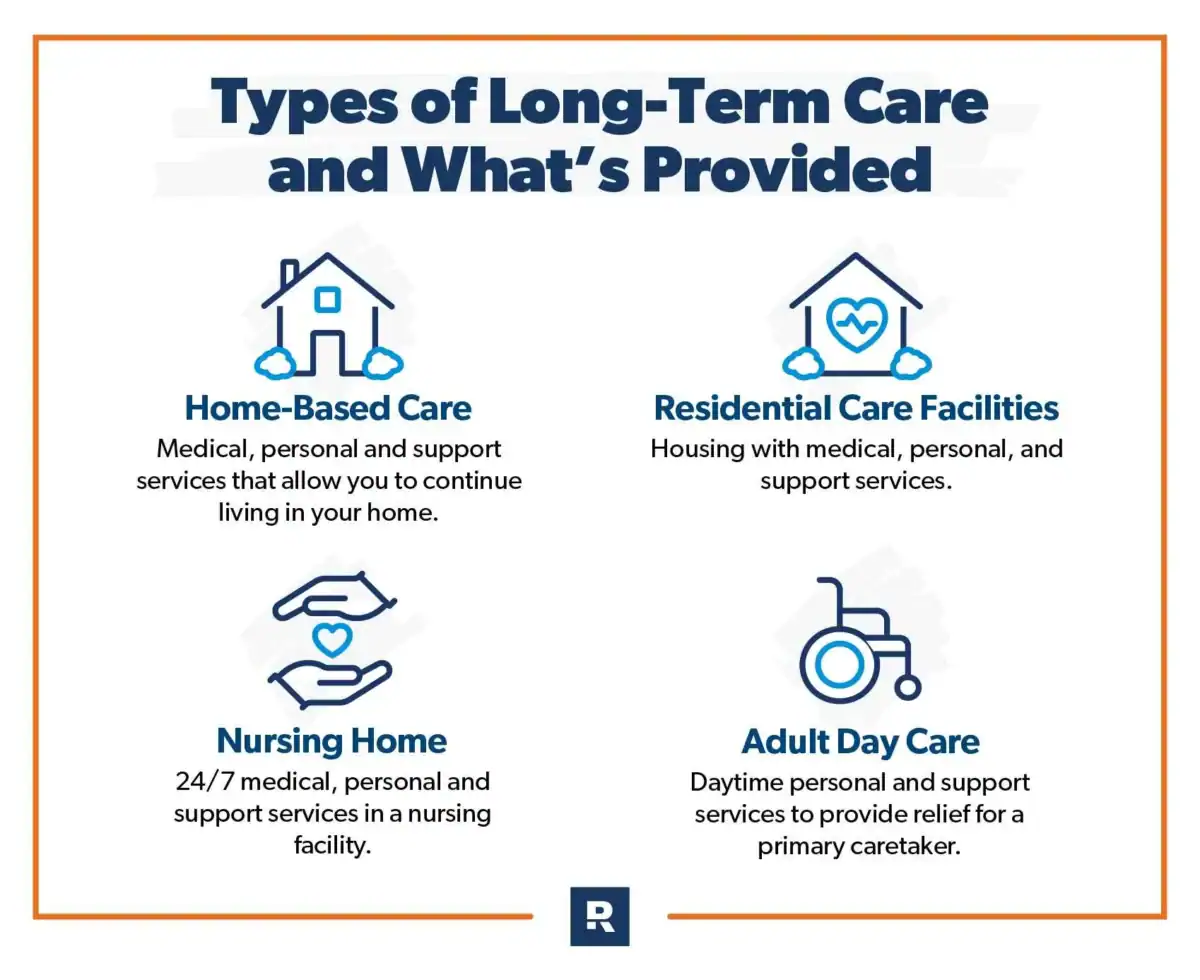

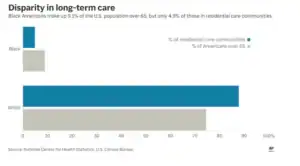

CLEVELAND — Ohio’s aging population is putting a growing strain on the state’s long-term care system, highlighting challenges with rising costs and uneven access to services. With an estimated 18.7 percent of residents age 65 or older, Ohio’s senior share is higher than the national average, according to America’s Health Rankings, which tracks state-by-state demographics and health indicators.

This demographic shift is colliding with a system that has long relied on institutional care, a pattern advocates say is costly and often runs counter to what most people prefer.

Systemic Issues and Cost Pressures

Ohio ranked 32nd nationally in AARP’s 2023 LTSS State Scorecard, which flagged particularly low marks on support for family caregivers, according to the Scorecard’s Ohio profile.

Ohio’s rebalancing toward home and community-based services has lagged the U.S. average: in fiscal year 2020, 57.6 percent of Ohio’s Medicaid LTSS spending went to HCBS compared with 62.5 percent nationally, as published in the federal Medicaid LTSS Expenditures Report.

Financial pressure is expected to build: inflation-adjusted Medicaid spending for long-term care is projected to rise from about 130 billion dollars in 2020 to 179 billion dollars by 2030, according to the Penn Wharton Budget Model.

Workforce shortages further constrain in-home options. In 2020, vacancy rates reached 17 percent for full-time and 27 percent for part-time direct support professional positions, the Ohio Department of Developmental Disabilities reported.

What Is Working in Other States

Other states have tested strategies Ohio could study, according to program documents and state agencies.

Public LTC trust: Washington’s WA Cares Fund provides a universal long-term care benefit funded by a 0.58 percent payroll contribution, with a lifetime benefit that is indexed to inflation and slated to be payable starting July 2026, according to the program’s official materials and employer guidance.

Expanded PACE access: California has significantly broadened the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly, CalPACE; industry and state sources note more than two dozen counties served and statewide expansion efforts to help people remain at home, according to CalPACE and related presentations.

Workforce investments: To combat shortages, Minnesota established tiered wage floors for personal care and CFSS workers beginning in 2024–2025 and set wage steps tied to experience, according to Minnesota Department of Human Services and state announcements. New York increased its home care worker minimum wage by 2 dollars per hour beginning October 1, 2022, per New York State Department of Health guidance. mn.gov // Minnesota’s State Portal+1New York State Department of Health

Nurse delegation: Oregon permits registered nurses to delegate certain tasks to unlicensed caregivers in assisted living and other community-based settings under Division 47 of the state’s Nurse Practice Act, as published by the Oregon State Board of Nursing and Secretary of State.

Public dashboards: Wisconsin publishes Family Care managed care scorecards, while Maryland’s Longevity Ready Maryland plan features a public data dashboard to track progress on aging-related goals, according to state program sites.

Potential Reforms for Ohio

Policy experts and advocates suggest several reforms Ohio could consider to improve long-term care services, stabilize the workforce, and manage costs.

Public LTC trust: Creating a public long-term care trust could help middle-income families finance nonmedical support at home and delay Medicaid reliance, according to early lessons from Washington’s WA Cares Fund.

Expand PACE: Expanding the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly into more metro areas and rural counties could reduce hospitalizations and support aging in place, as reported by California’s PACE association and state partners.

Workforce plan: A statewide workforce plan with wage floors, tiered experience ladders, and retention incentives could improve recruitment and retention, as seen in Minnesota’s multi-year wage framework, according to The Minnesota Department of Human Services (MDHS).

Medicaid managed care: Moving long-term services and supports into a managed care model with strong quality guardrails could improve coordination and control costs. Arizona’s mature ALTCS program has reported costs roughly 16 percent lower than a traditional fee-for-service baseline, as cited by the state’s 1115 waiver renewal. AHCCCS

Public dashboard: A statewide dashboard to track wait times, quality, and caregiver supports would increase transparency and accountability, following examples from Wisconsin and Maryland, according to those states’ public reporting. Wisconsin Department of Health Serviceslrm.maryland.gov

A number of states have shown it is possible to expand in-home access, stabilize the care workforce, and slow cost growth simultaneously, according to the sources cited above. With a clear plan and targeted reforms, Ohio could reshape its long-term care system to better serve an aging population in the coming decade.