By Lisa O’Brien

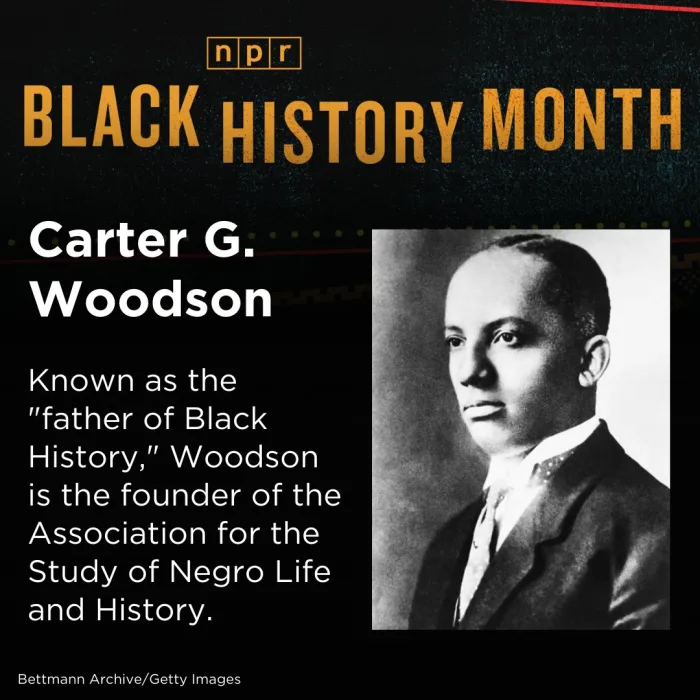

As February approaches, many people are familiar with Black History Month but not as many are familiar with the fact that the monthly celebration began here in Northeast Ohio at Kent State University. Black History Month began as just a week-long celebration in the second week of February called Negro History Week, started in 1926 by Carter G. Woodson. It wasn’t until 1970, after a year of advocating, that the first observance of Black History Month occurred at Kent State, six years before President Ford gave the month its formal national recognition.

It was students of Kent State’s Black United Students organizations that conceptualized and advocated for a whole month dedicated to Black history and excellence. They achieved their goals with support from faculty and staff, and one of these early students has now had the chance to pay it forward as Professor and Chair of Kent State’s Africana Studies program. That former student is current Professor Mwatabu Okantah, who I had a chance to speak with and ask a few questions about Kent State’s role in Black History Month:

Lisa: Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with us! To start, how do you feel that the celebration and observance of Black History Month have changed over your time at Kent State both as a student and now as a faculty member?

Okantah: It’s evolved. It all begins with Carter G Woodson. He is considered the father of what he called National Negro History Week and he launched that in 1926. But he founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History in 1915!…He believed in the importance of African American history…and Woodson in a sense was a part of the black consciousness movement at that time, early in the twentieth century. I go back to that because Black United Students at Kent State walked out in protest because they allowed the Oakland [California] police force to recruit on-campus [the students were protesting the Oakland police’s excessive use of force on the Black Panther Party and the killing of Bobby Hutton]. The university had to negotiate to get the students back [by meeting with leaders of the Black United Students and hearing their demands].

They demanded a Black Studies program, they demanded a Black cultural center, and they demanded more Black faculty and staff. So, in 1969 a man by the name of Edward Crosby was brought to campus and he founded the Black Studies program. That’s important because those students understood they were a part of a larger Black Studies movement that was going on at the time.

I arrived as a first-year student in 1970, so the upperclassmen at that time had participated in the walkout so I was groomed by them. In 1976, Gerald Ford as president signed off on it. In some ways, once that happened, in many places it became reduced to studying the names of “famous” people. It really moved away from Cart G. Woodson’s original intent. Where you go will determine how people will deal with it in terms of its depth.

L: And talking about the depth in how students celebrate the month, how do you feel that is specifically at Kent State right now?

O: Because our program is more than 50 years old, we have an academic unit, and we have a cultural center that provides our students with the depth and exploration of the entire experience. Which is what Carter G. Woodson intended.

L: What do you feel is the most important way institutions can support and empower their Black students on campus? Is it through the curriculum? Having designated spaces on campus? DEI programs?

O: It’s all of that. Think about it. We are talking about Black History Month. Now there is Native American History Month. Now there is Women’s History Month. Now there is a Hispanic/Latino History Month.

As a result of what Black students at Kent State did in terms of the Black Studies program, which is now the department of Africana Studies, we now have a women’s center at Kent State. There’s a Women’s Studies program at Kent State. There’s Latino Studies at Kent State. There’s LGBTQ Studies at Kent State. So all of those areas, all of that expansion, all of that progress, came out of this Black struggle. You now have programs like that all around the country. But the pushback that’s going on for your generation is the attempt to roll all of that back. You gotta wake up to stay woke!

L: That leads me right to my next question which is, with administration changes, there’s talk of increasing book bans and efforts to do away with DEI initiatives in secondary and higher education. How do you foresee this impacting the Africana studies program now or in the future, if at all? And what advice do you have for people to take things into their own hands and fight against these policies?

O: Black Studies have always been under threat from the very beginning. Our program was created against the will of the university. Back in the 1970s when I was a student, the opposition to our program came from within the university itself. We were not in a struggle against the university to destroy the university, which is what they thought. We were in a struggle to improve the university.

These things run in cycles, so now they are moving to move these things back. So if these things are going to be preserved, the current generation of young people is going to have to organize themselves to challenge the system and do what’s necessary. That’s what the Black Lives Matter movement was about. The current generation is waking up to see that what’s been happening to our people in the past is still happening.

When alumni come into the building, oftentimes they are moved to tears because that was the dream vision that we had in the 1970s. The fact that I’m now back as a faculty member resonates with me because I knew what it took for that building to be there. And if students don’t wake up to protect it, we could lose it.

L: Thank you. My next question is admittedly self-serving since I am a writer, but I know you are a poet. Do you have any recommendations of poets to check out specifically for Black History Month?

O: There’s a wealth of Black poets and you can divide it into the different periods. I am a product of the Black Arts movement of the 1970s. I was influenced by people like Nikki Giovanni, Gwendolyn Brooks, Haki Matubuti, Larry Neal, and Maya Angelou, and I’ve been blessed to have done readings with these people. And now I have students who’ve been published! L: Lastly, are there any events on campus in February you would like our readers to know about?

O: Yes! One of my part-time faculty members, Ismail Al-Almin, is a filmmaker. He produced an ESPN 30 for 30 documentary called “False Positive.” It’s about a world-class sprinter named Butch Reynolds who tested positive for steroids, but it was not his sample. And Professor Al-Almin has done this documentary about him. And we will be having a screening.”

The screening will take place February 17 at 7:30 p.m. in Oscar Ritchie Hall. Both Professor Al-Almin and Butch Reynolds will be present to answer questions about the films. Visitors can also see from now until February 7 the photo exhibit in the Oscar Ritchie Art Gallery which focuses on the history of Black United Students at Kent State.